Changing Tides by Sally Jensen

Liz didn’t write this cogent article on cli-fi in the movie world but she wishes she had. It’s by her niece Sally Jensen, and was first published in Film Stories Magazine. Enjoy.

Climate change depiction in mainstream cinema’s past, present and future

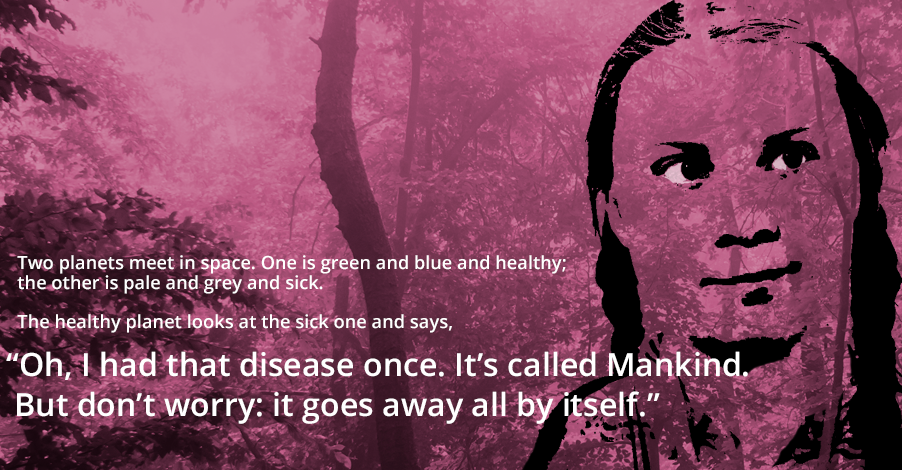

Opening scenes. A freak polar vortex blankets the US Midwest with snow, ice and bitter cold, bringing society to a standstill. After consecutive floods, droughts and cyclones, a city of 9 million people runs out of water. Record-shattering heat hits rich European countries, killing the most vulnerable and parching once-verdant hillscapes. Huge swathes of forest burst into flames around the globe, including in the most inhospitably cold places on the planet. Cracks appear in Antarctica’s ice shelf, on the verge of severing into an iceberg the size of Houston. Greenland’s ice sheet sheds 12.5 billion tons of water into the sea – in a day. Thousands of people are killed, and millions of people displaced, as homes are ravaged.

No, this is not a storyboard for the latest The Day After Tomorrow-esque apocalypse-flick. This stuff actually happened in 2019. For decades, Hollywood has been disturbingly obsessed with depicting in explicit detail the end of humankind and destruction of the planet. Now, it may have reality to contend with.

Set in fantasy universes degraded by resource scarcity, polar ice vortexes, hurricanes, famine and war, new films have defined the era of cli-fi, resurrecting the art of disaster porn in a new context of widespread ecological anxiety. While the 90s brought countless portrayals of human annihilation at the hands of extra-terrestrials and then robots, this century our fate is being controlled by nature, an ancient and elusive but no less merciless foe.

In Mad Max: Fury Road, which won six Oscars in 2016, climate catastrophe provides the backdrop for a civilization ripped to shreds by an energy crisis: an arid wasteland teeming with outlaws hoarding resources and killing each other for necessities. NASA’s water scientist Dr. James Famiglietti has ominously said “There are metaphorical elements of Mad Max that are already happening, and that will only worsen with time.” As a dystopian action film, the intrigue revolves around the coping mechanisms and interactions between the characters, placing its thrills in the shrieking lunacy of desert races and gruesome blood transfusions rather than the comparative stasis of the environment. In The Day After Tomorrow by contrast, nature plays a more active role, replacing a traditional villain figure with something far more unpredictable, omnipotent and whose brains it’s less easy to blow out with a gun. The plot develops parallel to the calamity, as hurricanes bring international polar ice vortexes, instantaneous sea-level rise and hailstorms. The scale and swiftness of the catastrophes depicted represent the ultimate conflation of what defines weather versus climate. However, in spite of its excessive scientific inaccuracy, which was criticised for being harmful to the climate cause, the captivating interplay between nature’s brutality and the empathetic protagonists caught in its wrath made it a huge success, becoming the sixth-highest grossing movie of 2004.

A precursor to Mad Max: Fury Road, Waterworld similarly forewarns of the violent conflict that arises thanks to resource depletion, except with savages zooming around on speedboats rather than 4WDs. Released in 1995, it probably didn’t anticipate how soon the future it depicts would come to pass. Although the film was a flop, it’s worth revisiting if only for its eerie prediction of rising sea levels; a world where basic survival is pitted against human empathy. While in both these action films the dystopian element is basically a fait accompli, in Interstellar crop blights and dust storms are a looming threat much like they are today. Firmly in the McConaissance catalogue, human salvation lies in one smart guy’s martyrdom, but also selflessness is key: “we must think not as individuals, but as a species.” Bringing to life the ideology of so many tech bros, space nerds and venture capitalists, escapism is the answer in this box-office smash: “We’re not meant to save the world – we’re meant to leave it,” says Michael Caine, in true Elon Musk form.

In all these, as with other apocalyptic cli-fi blockbusters (Geostorm, 2012, The Colony, Snowpiercer), the limelight is on humanity’s story and struggles in the face of these challenges, following the usual trope: hero, usually a male scientist/father/likeable figure (most likely white, except in The Colony), faces up against climate-induced chaos which threatens people he cares about; appeals to a reluctant higher authority for assistance; chaos exacerbates posing a threat to wider humanity; hero and allies ‘single-handedly’ find a solution; annihilation averted by some feat of geoengineering or sheer luck. (It’s the blueprint for the popular meme that all disaster movies start with the government not listening to a scientist – an acute observation of the era we live in.) The focus on human protagonists is nothing if not pure Hollywood: take out the interpersonal relationships, treachery, love, crying children, and you’re left with a baked landscape decimated by the odd hurricane and token tsunami, which wouldn’t attract the same viewing figures. Natural disasters couldn’t care less about humans, yet Hollywood inherently does. But will climate change cinema always follow this convention? And what is its true purpose?

Even today, when most people think ‘climate change movie’, they think Al Gore standing on a stage pointing at Powerpoint slides. But while An Inconvenient Truth ushered in a wave of fact-based climate documentaries (Chasing Coral, Ice On Fire) which can’t legitimately be criticised for inaccuracy, their failure has arguably been in not telling an engaging enough human story to reach mass audiences. Granted, Before The Flood benefited from Leonardo DiCaprio’s magnetic narration and promotional savvy, but it didn’t stop many from complaining that its realism was way too depressing. (A more apt criticism might be that it has become too common and easy for celebrities of his ilk to take a role in mainstream cli-fi, using it as a platform to showcase their newfound wokeness, rather than actively shun the global system of extraction and exploitation which simultaneously fuels the issue and their success.)

It’s a challenge of planetary proportions to make accessible, accurate, representative movies about the current state of ecological chaos. There’s a question to be asked of whether Hollywood, with its overindulgence in violence, sentimentality, money and excess is even compatible with serious science. But it’s not like effective climate movies don’t exist – indeed many have won awards in recent years. Beasts of the Southern Wild, while perhaps nuancing on the climate issue, is an incredibly moving human story that deals with the social consequences of extreme weather and its intersection with racial and class oppression. Similarly, The Boy Who Harnessed The Wind, benefiting from Chiwitel Ejiofor’s leadership, brings the harsh imagery of actual climate desperation to privileged audiences, and ends with a small but hugely emotional message of hope. It’s worth including Deepwater Horizon here too, which although it doesn’t touch directly on climate change, it does a good job of condemning oil disasters and fossil fuel execs for their role, who exploit workers and resources for dirty profit. Even Snowpiercer pierces into the question of social inequality, unrest and revolution – not new for sci-fi, but perhaps a first in the context of cinematic climate change storytelling.

Meanwhile, the somewhat forgotten Idiocracy, while recently receiving attention for its prescience of US political circumstances, is actually a rare and highly creative climate change comedy. 500 years into the future, the snowballing stupidity of humans has led to a dust bowl, crop failure and trash peaks, as well as deteriorated health and hygiene. It turns traditional climate change storytelling on its head, making us cry but with laughter, pinning the blame firmly on us, everyday Westerners, for our apathy. While it doesn’t solve everything, the triumph of putting water (“Like, from a toilet?”) on soil taunts the way we overlook basic natural solutions in favour of quixotic geoengineering. The hero is literally an Average Joe.

While these tales both inform and entertain, the larger question is whether the purpose of climate change cinema would be to instigate action from where it would make most difference, i.e. kick mainstream Western audiences up the backside. In fact, some of the most hopeful and interesting stuff is being made for those with everything to live for – children. The meltdown in Ice Age: The Meltdown, while not anthropogenic, serves to instil a fear and awe of nature’s unpredictability and create a sense of powerlessness at giant ecological shifts, not to mention empathy with endangered non-human animals (some things are so much easier with children). Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs is underrated as a commentary on climate breakdown, perhaps because at a first glance, a movie about a world where it rains food seems too wacky to take seriously. But it warns of the consequences of worldly avarice: be careful what you wish for, or you just might cause a spaghetti tornado to rip through your town.

Dr. Seuss, being way ahead of his time, of course knew about the importance of protecting nature and biodiversity. But The Lorax’s feature-film release in 2012 was all the more poignant and necessary given the era of mass ecological decimation and elitist greed kids are now growing up in the midst of. The song ‘How Bad Can I Be?’ is a catchy anthem condemning corruptibility and corporate fat cats. The whole thing teaches kids (and adults) that if we do not collectively take responsibility for environmental stewardship, then our own world will soon be a wasteland with no trees or friends.

With animated movies like these, future generations might watch Titanic and feel bemused that an iceberg threatened the existence of people (especially, ironically, Leonardo DiCaprio), rather than the other way around. For too long, mainstream climate cinema has not focused on the causes but the effects of climate change, as it fits so nicely with the need for a heroic storyline. By omitting the ‘man-made’ origins or any of the processes leading up to disaster, there is the tendency to absolve humans of responsibility. What’s more, it usually conveniently skirts around existing social issues of race, class, and gender which are exacerbated by climate breakdown, lumping humanity into an evenly susceptible or responsible mass. While Interstellar is right to emphasise thinking as a species, it is wrong to suggest there’s nothing to be done. We are cast as powerless actors in the fate of external forces, to be rescued by other external forces; rather than individuals with the capacity to hold ourselves accountable and create change.

But perhaps this is too much to ask of Hollywood, which is not known for a history of creating mass movements and social upheaval. It is there to entertain, not preach. Regardless, climate change is becoming ever more real and present in our lives, and all directors and producers should be preparing themselves for integrating these realities ever more in their depictions of everyday life. It won’t be long before we start seeing romcoms, spy thrillers and arthouse dramas set in a world of climate crisis; the same way the theme has already taken hold in our sci-fis and is slowly creeping into the realm of action movies. It’s probable that the generation learning about the impending ecological crisis from today’s colourfully animated 3Ds and CGIs may have to live through mass global displacement, disease, flooding and extreme weather events on a regular basis. It will become the norm for this to be reflected on the big screen, if enjoying cinema has not already taken a backseat to other existential priorities by then. If it hasn’t, the corporate fat cats had better watch out – there’ll be a slew of biographical hard-hitters waiting for them.